Juniper Publishers-Journal of Ophthalmology

Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate clinical safety and

efficacy of a novel use of an ocular tissue adhesive in Descemet’s

Stripping (Automated) Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK).

Methods

35 consecutive DSAEK cases were

evaluated retrospectively. In group-A (nA=15) the tissue adhesive (Re

Sure Adherent Ocular Bandage, Ocular Therapeutix, Inc., Bedford, MA) had

been used, prior to placement of one suture, while in group-B (nB=20),

only nylon sutures were used for the closure of corneal incisions.

Peri-operative complications were noted. Visual Acuity, refraction and

topographic cylinder, Intraocular Pressure (IOP), and endothelial cell

counts (ECC) were monitored long-term for up to two years.

Results

Follow-up time was 10.5±8.5 (8 to

29) months. No case from group-A required any additional air insertion

following the tissue adhesive application and no case required

additional intra operative surgical manipulation for further graft

centration. In group-B eighteen (out of twenty) cases required

intra-operative supplemental air insertion, and four of those

intra-operative repositioning of the graft. The differences in visual

acuity and IOP were not statistically significant; ECC change of -16% in

group-A vs. -21% was noted in group- B (statistically significant, p

=0.03). Hyperopic shift was noted in both groups; cylinder reduction was

noted, too, with group-A performing better.

Conclusions

Tissue adhesive may be a valuable

adjunct in clear-cornea DSEAK by stabilizing the potential of air

escape from the main incision inadvertently occurring during suture

placement.

Keywords: LED Cassini;

multi-color LED topography; Acanthamoeba keratitis; Point-source

topography; Pentacam HR; Placido topography; Scheimpflug topometry;

Differential topography; Irregular corneal astigmatism; Stray light

measurements; C-Quant; Anterior-Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

Introduction

Descemet’s Stripping (Automated) Endothelial

Keratoplasty (DSAEK) surgery has become the standard of care worldwide

for endothelial dysfunction management [1] superseding for this purpose

Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK). PK involves a full corneal thickness,

open-chamber procedure; among the disadvantages noted with this

procedure are the prolonged visual rehabilitation, unpredictable

cylindrical refractive changes (high postoperative astigmatism),

susceptibility to ocular surface complications (wound dehiscence), and

vulnerability to traumatic wound rupture [2,3].DSAEK, introduced 2002,

[4] involves the posterior cornea lamellae in a closed-chamber procedure

[5]. Because of this, it is considered safer, provides faster visual

recovery, [6] usually requires only few sutures and causes less

astigmatic change,[7] overcoming some of the limitations of PK.

The corneal incisions associated with ocular corneal

surgery, such as cataract and lamellar keratoplasty, are becoming

smaller, depending on surgical instrumentation and techniques, as well

as on implantation materials and designs. There is, nevertheless,

concern that closure of DSAEK incisions with nylon sutures may induce

air-bubble escape and possible graft slippage. Additionally, astigmatic

changes may affect visual function. We have observed during our

experience with DSAEK [8] topographic and tomographic changes consistent

with significant irregular astigmatism along the incision site.

Application of ocular tissue adhesives for the

closure of corneal incisions in DSAEK is considered a novel approach.

This technique carries the benefits of an absence of risk of

intraoperative needle stick injury and later suture removal. The purpose

of this study was to evaluate the clinical efficacy of ocular tissue

adhesive application in DSAEK cases.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective case series study received

approval by the Ethics Committee of our Institution, adherent to the

tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent for the

anonymous use of data had been obtained from each subject at the time of

the first clinical visit or prior to the operation.

Inclusion Criteria

All consecutive DSEAK cases in our institution were

considered for this study. The decision to proceed with ocular tissue

adhesive-assisted closure (group-A, nA= 15 eyes) or traditional

nylon-suture closure (group-B, nB= 20 eyes) or was based on random

choice (coin toss). No case included in the study involved concurrent

cataract removal and/or intraocular lens replacement surgery, which in

our clinical practice corresponds to near 1/3 of the DSAEK operations.

All cases were performed by the same surgeon (AJK), as an ambulatory

outpatient surgery procedure (not requiring hospital admission), and

under monitored local anesthesia with peribulbar block [9].

Surgical Technique

We prepared the DSEAK grafts ourselves, with a Moria

artificial chamber (Moria Surgical, Antony, France), an LSK (Gebauer

Medizintechnik GmbH, Enzkreis, Germany) microkeratome (350 μm

microkeratome head), and a Hanna suction punch block (Moria). Typical

central graft thickness was of the order of 120 μm. A main clear cornea

4.50-mm incision at the 9th hour was employed for implantation using the

singleuse Busin glide spatula #17300 (Moria SA, Antony, France).

Additionally, two clear cornea paracenteses were performed, a 1-mm at

the 6th hour for a Moria coaxial microforceps forceps insertion and a

1-mm at the 3rd hour for the anterior chamber maintainer insertion and

infusion. The DSEAK procedure was otherwise standard, to include scoring

the host Descemet’s with a reverse Sinskey hook, removal of the central

hosts Descemet’s membrane, and bi-manual pull of the DSEAK graft

through the Busin glide spatula with forceps placed through the anterior

chamber. Following the graft lenticule insertion in the anterior

chamber, the anterior chamber maintainer infusion was restarted and the

graft was unfolded. Last, a large air bubble was introduced in the

anterior chamber in order to secure superior tamponade of the graft,

against the host cornea. Following this last step, the two groups had

different completion.

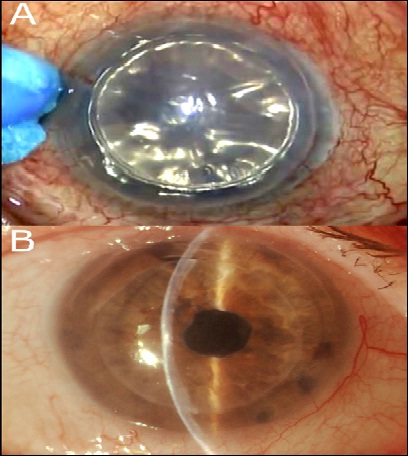

In group-A, the tissue adhesive (ReSure Adherent

Ocular Bandage, Ocular Therapeutix, Inc., Bedford, MA) was mixed on the

operating instrument stand, and applied in liquid form (painted) on the

main incision borders with a special spear sponge following the

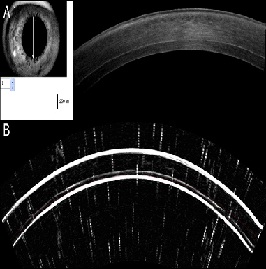

absorption of any redundant surface fluid (Figure 1A). Within 3 to 5

seconds, the material was stable in soft form and any excess over the

peripheral conjunctiva was removed with a dry spear sponge. The eye was

observed for an additional 45 minutes for graft stability while the

anterior chamber was filled with at least 75% with air and air

tamponade, only the ‘matress’ 10-0 polypropylene sutures employing the

CS 160-6 needle (Ethilon, Ethicon Inc, Somerville, NJ) were placed to

secure the main incision. The sutures were removed typically at the

one-month visit; in all cases the sutures had been removed well prior to

the threemonth scheduled visit.

Data Collection and Analysis

All patients had been evaluated pre-operatively and

at least one-year post-operatively for best-spectacle distance corrected

visual acuity (CDVA) reported decimally, spherical and cylindrical

error reported in diopters (D), Intraocular pressure (IOP) reported in

mmHg, and endothelial cell density (ECC) reported in cells/mm2. In the

case of pre-operative ECC, the data from the cornea bank certificates

were used, while post-operatively, ECC was measured by specular

microscopy (FA-3709, Konan Medical, Irvine, CA). Slit-lamp evaluation

was also part of the complete ophthalmological evaluation performed.

Figure 1B illustrates an example of slit lamp imaging from a sutureless

DSEAK with the use of tissue adhesive, 1 week post-operatively.

Spherical and cylindrical error corresponds to the

refraction for which the CDVA was reported, and was based on phoropter

manifest refraction examination. IOP values were not adjusted for

corneal thickness changes. In addition, qualitative evaluation by means

of corneal tomography (Pentacam, Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar,

Germany) and anterior-segment as well as retinal optical coherence

tomography imaging (RtVue-100, Optovue, Fremont, CA) were part of the

standard protocol performed during all visits [10]. Figure 2A presents

an example of OCT imaging performed on DSAEK case two years

postoperatively. Whenever possible, high-frequency scanning ultrasound

imaging (Artemis ii+ superior, Artemis Medical Technologies Inc.,

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) was also employed for the imaging

of the anterior segment. An example of Artemis cross-sectional imaging

is illustrated in Figure 2B. Due to the nature of the condition,

post-operative recovery was followed for at least once a year past their

12-month visit in all cases.

Results

The subject age in group-A (nA=15, 5 male and 10

female, 8 OD and 7 OS), at the time of the operation was 72.94±15.59 (36

to 90) years, while in group-B (nB=20, 6 male and 14 female, 9 OD and

11 OS) was 69.57±11.9 (50 to 88) years.

No case from group-A required any additional intra

operative air insertion following the tissue adhesive application and no

case required additional intra operative surgical manipulation for

further graft centration. No case required post-operative rebubbling or

had any graft rejection incidence.

In group-B, 18/20 cases required intra-operative

supplemental air insertion (re-bubbling), and four of those,

intra-operative graft repositioning. Additionally, five cases required

post-operative re-bubbling (on average 5.7 months post-operatively), and

one case lead to graft rejection, followed by penetrating keratoplasty 9

months from the initial DSAEK operation. The cases from group-B with

post-operative rebubbling

or graft failure were excluded from the subsequent data analysis,

leaving thus 14 cases whose refractive data are reported in this study,

of which 4 were female and 11 male; 7 belonged to right eyes (OD) and 8

to left eyes (OS). Average follow-up time for all cases was 10.5±8.5 (8

to 29) months.

In group-A preoperative CDVA was 0.14±0.17 (0.01 to

0.60) decimal, spherical error was -1.05±3.30 (-9.50 to +4.00) D,

cylinder was -3.75±2.05 (-10.50 to -0.50) D, IOP was 17.25±5.60 (10 to

29) mmHg, and graft/donor ECC was 2,567±310 (1,790 to 2,935) cells/mm2.

In group-B pre-operative CDVA was 0.15±0.16 (0.01 to

0.50) decimal, spherical error was -0.94±3.60 (-12.50 to +5.00) D,

cylinder was -3.24±2.44 (-10.00 to -0.25) D, IOP was 18.83±6.02 (8 to

32) mmHg. Graft (donor) ECC was 2,440±532 (1,635 to 2,850) cells/mm2.

Table 1 summarizes the pre-operative as well as the

3-month and 12-month refractive and corneal data pertaining the two

groups of study. The two groups were matched on all aspects of the

parameters involved in the study (age, gender laterality, eye

laterality, visual acuity, sphero cylindrical error, IOP and graft ECC),

as none of the paired-test p-values was less than 0.05.

The improvement in visual acuity within the same

groups had a noted and statistically significant improvement at the

3-month interval (Δ = +0.22 and +0.10 for group -A and –B, respectively)

as well as at the 12-month interval (Δ = +0.31 and +0.25). IOP was

increased (Δ = +5.51 and +4.65 mmHg for group-A and –B, respectively) at

3-months as well as at 12-months (Δ = +5.77 and +5.22 mmHg). The

increase in IOP between the two groups was rather similar, and not

statistically significant. ECC change at 12-months of -16% was noted in

group-A vs. -21% in group-B (statistically significant difference

between the two groups, p =0.03).

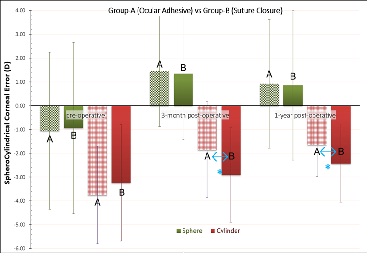

Figure 3 illustrates the sphero cylindrical error

(sphere and cylinder) pre-operatively, as well as 3-months and at

12-months

post-operatively. The spherical error indicated a hyperopic shift of

+1.97 D in group-A and +1.79 D in group-B (not statistically significant

difference between the two groups). Cylinder was improved (reduced), by

2.10 D in group-A, and by 0.81 D in group-B. The difference of cylinder

improvement between the two groups was statistically significant (p

=0.012).

Discussion

Management of surgical cornea incisions with nylon

sutures may have been the acceptable standard in the past, but there are

a number of complications associated with this technique [11]. Induction

of astigmatism, potential to fluid ingress and egress from the ocular

surface,[12] endophthalmitis, [13] and increase of surgical time and

patient discomfort are some that may be listed. There is, therefore,

interest in an adhesive to replace and/or supplement sutures in the

repair of corneal wounds and improve corneal incision sealing [14]. The

material must

be biocompatible, self-dissolving, and safe (eg without affecting visual

function).

Cyanoacrylate, a biocompatible material, has long

been employed in surgical incisions [15]. The latest cyanoacrylate

adhesive for medical use, FDA-approved in 2002, was n-butyl-2-

cyanoacrylate (Indermil®, Vygon-Ecouen, Lansdale, PA). It has been used

to close small skin wounds in pediatric patients, with successful

results [16]. Applications in ocular surgery have also been reported

[17,18].

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymers are also among the

materials considered for corneal wound sealing [19]. Biocompatible PEG

polymers form the same type of hydrogel used in contact lenses in

wetting agent applications [20]. The liquid hydrogel compound is

administered (painted) over the wound, and polymerizes fast (in

approximately half a minute) into a soft form that adheres to the ocular

surface, forming a bandage that leads to a watertight seal. Two such

ocular tissue adhesive products are the ReSure (Ocular Therapeutix,

Inc., Bedford, MA) [21] and the OcuSeal (BD Medical, Waltham, MA) [22].

Ocular tissue adhesives have been evaluated for their

applicability in limbal-conjunctival wound after fornix-based

trabeculectomy [23] and cataract surgery [24]. To the best of our

knowledge there is no report in the peer-reviewed literature on the

topic of ocular tissue adhesives in DSAEK.

The present work is to the best of our knowledge the

first investigation that presents the clinical applicability of

employment of ocular tissue adhesive in DSAEK. We evaluated

comparatively two matched groups of study over a long followup period.

The differences in regard to far fewer cases needing intra-operative

re-bubbling have been compelling. Postoperatively, similar visual acuity

and IOP changes are noted. CDVA was improved in both groups, while also

IOP increase has been noted; the latter can be explained by the thicker

cornea (as a result of the DSAEK procedure) and the known dependence of

IOP readings on central corneal thickness [25].

We noted a statistically significant ECC loss in both

groups (by -16% in group-A, and by -21% in group-B). These data are in

accordance with published results in the literature. For example, ECC

loss of -19% has been reported in DSAEK cases [26]. We note, however,

that the ocular adhesive group-A appears to perform better in this

aspect (p =0.045 between the two groups).

Regarding the refractive data, both groups indicate a

significant hyperopic shift. The average increase in sphere was more

than +2.50 D at the 3-month interval and near +2.00 D at the 12-month

interval. This hyperopic shift has been modeled, and the average

predicted hyperopic shift in the overall power of the eye was calculated

to be +0.83 D [27]. It is explained by the fact that the graft is

thinner centrally, as a result of the microkeratome pass creation

procedure over the donor cornea, and the known increased corneal

thickness peripherally. It appears that our technique introduces more,

but predictable hyperopic shift. As a result the graft is thinner

centrally and thicker peripherally, the ‘new’ posterior corneal surface

has a smaller radius of curvature; our calculations based on application

of the Gullstrand’s formula indicate that for approximately 1 mm change

in the posterior curvature (e.g from 6.8 to 5.8 mm) there is a

corresponding 1.00 D change in the posterior corneal refractive power

(e.g. from -5.88 D to -6.90), resulting thus in 1.00 D of hyperopic

shift.

A noted improvement in cylinder was noted in both

groups, with the ocular adhesive group-B appears to perform better in

this aspect (p =0.032). The sutureless group-A had 12-month improvement

in cylinder by 2.1 D, while the suture group-B by 0.8 D. This may be

explained by the reduced effect on cornea distortion by the ocular

adhesive. Considering the nonsymmetrical nature of the suture placement

in the traditional wound sealing, the noted improvement in

surgically-induced astigmatism in the sutureless group-A may offer

perhaps the clinical advantage over the traditionally applied technique.

Application of a material that seals wounds safely,

effectively, and comfortably enable better suture placement and possibly

improve corneal surgical outcomes. This procedure enables better suture

placement and provides the benefit of the reduction of wound leak

during suturing and possible graft slippage. This procedure may also be

applied to DMEK cases. Further studies involving the clinical impact of

the use of these new polymer corneal sealants may be warranted.

Conclusions

This novel tissue adhes ive may be a valuable adjunct

in sutureless DSEAK clear cornea surgery in enhancing intra operative

anterior chamber stability and possibly offering more secure wound

closure.

Figure 2: Cross-sectional imaging of a DSAEK case two years postoperatively: top, utilizing anterior-segment OCT, and bottom, utilizing high-frequency scanning ultrasound.

Figure 3:

Comparative spherocylindrical error between the two groups,

pre-operative, 3-months and 1-year post-operatively. *indicates

statistically significant difference between the two groups.

For more articles in JOJ Ophthalmology please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jojo/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jojo/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment