JUNIPER

PUBLISHERS- JOJ Ophthalmology

Case Report

A 77 year old female approached our clinic due to a

progressive visual acuity deterioration lasting several years. She has

been diagnosed with primary Sjögren’s Syndrome for the last 5 years,

with keratoconjunctivitis sicca, Xerostomia and arthritis. Other medical

history included ischemic heart disease and hypertension. Her regular

medications included Amlodipine, Tritace, Cadex, Cardiloc, Plaquenil 400

mg and artificial eye lubricants (saline tears x6/d and Viscotears®

Liquid Gel x1/d). She denied use of punctal plugs or topical

cyclosporine use. On her initial examination best corrected visual

acuity was 6/30 in the right eye and 6/20 in the left eye. Slit lamp

examination showed diffuse superficial punctate ephithelial erosions

(SPK). Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 10 in both eyes. The lens had

nuclear sclerosis and anterior capsular opacity. The retina showed

peripapillary atrophy with mild retinal pigmented epithelium changes. On

April 2015 she underwent uncomplicated right eye cataract

phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intra-ocular lens (IOL)

insertion. First day post operative exam showed no change in visual

acuity, cornea with diffuse SPKs, mild descemet membrane folds with +1

cells in the anterior chamber (AC). Postoperative treatment was topical

Diclofenac (a local NSAID) and Maxitrol (Neomycin sulphate, polymyxin B

sulphate and dexamethazone) drops, 4 times a day each. Artificial tear

drops were continued.

Seven days post operatively, examination revealed

that visual acuity remained 6/60 PH 6/30. The cornea had diffuse dense

SPKs with epithelial edema and a small bulla appeared on the lower half.

The patient was asked to gradually lower the medical treatment dosage.

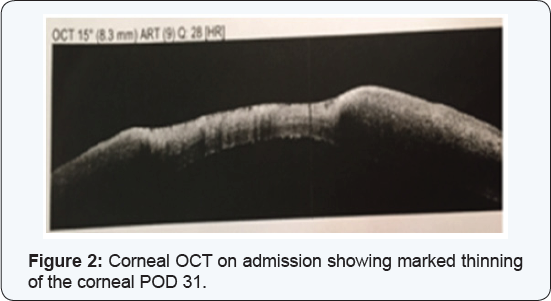

At the next routinely scheduled postoperative examination

(post-operative day 30), a large inferior para-central corneal erosion

was observed (Figure 1) and corneal OCT showed a significant thinning in the erosion area (Figure2).

The patient reported no pain and didn’t notice any vision

deterioration. On further history, the patient misunderstood her medical

regime and continued both steroidal and NSAIDs drops without lowering

the dosage. She was admitted for hospitalization.

On admission exam visual acuity was 1 meter finger

count (FC), the erosion size was 4.5 mm X 4.2 mm, no infiltrate was

seen, the AC was clear without cells or flare and the PC-IOL was in

place. Serum 20% drops every hour, Erythromycin ointment 4 times a day

and oral Doxycycline 100 mg per day were administered. Maxitrol and

Diclofenac were discontinued. PCR for Herpes Simplex and bacterial

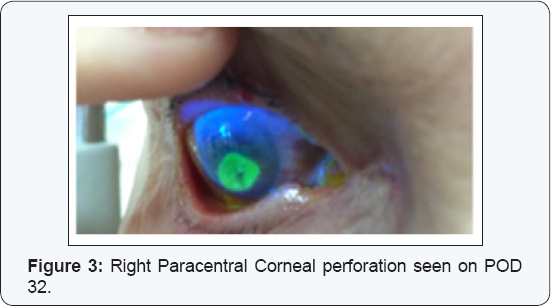

cultures were performed with a negative result. On the second day of

admission visual acuity deteriorated to hand motion. Slit lamp

examination demonstrated a slightly inferior paracentral corneal

perforation (Figure 3). The AC was shallow and the iris prolapsed through the corneal perforation.

The cornea was glued with cyanoacrylate and a

therapeutic contact lens was placed. Considering corneal melting due to

an inflammatory systemic disease systemic Prednisone 60 mg per day was

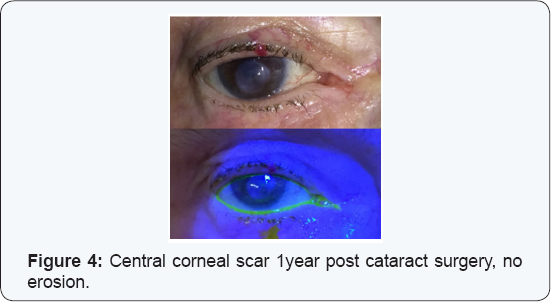

initiated. During clinic follow-up the glue remained on the cornea for

about 10 months and a therapeutic contact lens was replaced several

times. After 10 months the glue fell off, at first with a positive

Seidel test but at the concurrent visit there was no more leakage. The

cornea remained with a central corneal scar with no erosion (Figure 4)

and visual acuity did not improve. The patient and her family were not

interested in performing rehabilitative corneal procedures, due to her

system illness.

Discussion

Sjögren’s Syndrome is a progressive autoimmune

disease characterized by lymphocyte infiltration of the exocrine glands

resulting in their fibrosis causing keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry

eyes; 85% of patients) and xerostomia (dry mouth; 90% of patients) with

several systemic manifestations, [1].

The disease affects mostly women (9:1 ratio) with median age of 54

years. Positive serum serology for Anti SSA (RO) or Anti SSB (LA) is

found in about 60% of patients. The current diagnostic criteria for

Sjögren’s syndrome include ocular or oral symptoms and 2 out of 3 the

following: Positive serum serology (antiSSA and/or antiSSB or positive

rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody titer >1:320), salivary

gland biopsy showing tipical lymphocytic sialadenitis (with a focus

score >1 focus/4 mm2) and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (ocular staining

score >3) [1] (Table 1).

The disease is slowly progressing, taking about 10 years from onest until the complete clincal expression is demonsterd[2].

From the ophthalmic point of view the most important symptom is

keratoconjunctivitis sicca, secondary to the lack of tears in the eye

tear film, with destruction of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium.

Treatment is mainly sympthomatic with lubrication or nasolacrimal duct

occlusion. Immunomodulatory treatment as local Cyclosporine has also

been suggested in difficult cases. For systemic manifastations,

treatment may incude Hydroxychloroquine, Methotrexate and Prednisone [2].

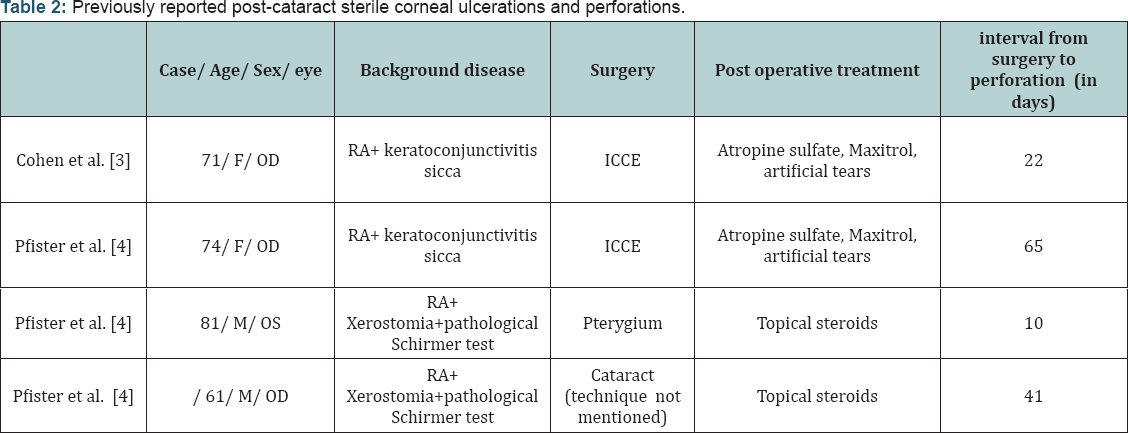

F- Female; ICCE- Intracapsular cataract extraction; RA- Rheumatoid arthritis.

Post-cataract sterile corneal ulcerations and

perforations in Sjögren’s patients has been previously reported in only

two articles, (Table 2) [3,4]. Cohen et al. [3]

reported two females with a prolonged history of rheumatoid arthritis

and keratoconjunctivitis sicca that developed painless sterile corneal

ulceration and perforation following an uneventful cataract surgery

(Intracapsular extraction) [3].

Both patients received postoperative topical steroid drops. As in our

case report, perforations occurred within 3 to 8 weeks following

surgery. Pfister & Murphy [4]

reported on 18 eyes of 14 rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s patients

who had spontaneous corneal ulceration and perforation. Two of the case

occurred following an anterior segment surgery and topical steroid

treatment, one occurred 10 days post Pterygium excision, and the other

cases occurred 42 days post cataract extraction (technique not

mentioned) [4]. Reasons for the perforations in these cases may be divided to:

- A basic anterior segment disease.

- Surgical damage.

- Post-operative injury by topical corticosteroid/ NSAIDS treatment. Strategies for the timely diagnosis and proper management of dry eye syndrome in the face of cataract surgery patients will be emphasized.

A basic anterior segment disease

Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome may be at a high

risk for complications due to the chronic inflammatory state in the

anterior segment. Sjögren’s Syndrome is characterized by tear film

abnormality and epithelial damage; both are risk factors for

post-operative complications. A study that analyzed corneal innervations

and morphology in primary Sjögren’s Syndrome showed that in comparison

to controls the corneas of Sjögren’s patients had an irregular and

patchy surface epithelium, stromal thinning and that their sub-basal

nerve fiber bundles revealed abnormal morphology [5].

Moreover, in a study following 163 Patients with

Sjögren’s Syndrome, 13% had vision threatening symptoms- 4.5% had

spontaneous corneal melting or perforation during median 3 years follow

up, without any ocular surgery [6].

A chronic ocular inflammation state such as in Sjögren, scleritis or

uveitis patients should be controlled pre-operatively to minimize the

chance of scleral or corneal necrosis. The ophthalmologist can work in

conjunction with other physicians involved in the patient’s care to

consider systemic therapy with systemic corticosteroid and

immunosuppressive agents.

Surgical damage

Anterior segment surgery may cause corneal dryness

and damage by mechanism of post-operative corneal denervation and

reduced blinking rate. During surgery the cornea is exposed for a long

time without blinking which can also contribute to its dryness. Adding

ocular surgery to essentially dry eyes was found as a risk factor for

complications post anterior segment operations [7,8].

Post operative Topical corticosteroid and Non Steroidal treatment

Severe stromal melting has been reported with the

postoperative use of several topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs). The melting is due in part to the epithelial toxicity

and hypoesthesia that these drugs can induce. In addition topical

steroids suppress corneal wound healing by reducing collagen synthesis [9].

Management of corneal perforation

Persistent epithelial defects accompanied by stromal

lysis require intensive treatment with non-preserved topical lubricants.

The use of topical medications, particularly preserved medications,

should be minimized to reduce epithelial toxicity. Additional treatment

modalities to encourage epithelialization and to arrest stromal melting

include punctal occlusion, bandage contact lenses, tarsorrhaphy,

botulinum injections to induce ptosis, autologous serum eye drops and

systemic tetracycline antibiotics [10].

If the disease continues to progress in spite of medical therapy, an

amniotic membrane graft or lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty should

be considered. Corneal melting may recur even with grafted tissue. For

the treatment of any underlying autoimmune disease, systemic

immunosuppressive therapy may be needed. To note, the prophylactic use

of topical antibiotics must be monitored closely; after a week of

application, many topical antibiotics begin to cause secondary toxic

effects that may inhibit epithelial healing.

Managing patients with high risk for perforation prior to surgery

Abnormalities in the tear film may have an impact on

the ocular surface and thus adversely affect postoperative recovery if

not addressed in advance. Bringing the patient to the optimal epithelial

state prior to surgery will reduce future post-operative complications.

Preoperative excessive lubrications, punctual plugs and even temporal

tarsorrhaphy should be considered[11].

During the surgery itself, we suggest frequent hydration the cornea

with an irrigating solution or by coating the cornea with a topical

viscoelastic agent, in order to reduce such complications. Close

observation of these patients during the weeks following surgery is

warranted to identify and treat toxic keratoconjunctivitis and corneal

ulceration from collagenase activation by postoperative corticosteroid

therapy. Topical NSAID should be used with caution and with close

monitoring for these patients because they have the effect of reducing

corneal sensitivity and thus associated with high risk for corneal

melting [9].

In extreme cases, persistent epithelial defects may require a bandage

(therapeutic) contact lens, tarsorrhaphy, or amniotic membrane

transplant.

Optimizing dry-eye therapy prior to cataract surgery improves visual outcomes [7].

A variety of aqueous layer supportive treatments can be personalized

for each surgical candidate, including topical preserved and

non-preserved liquid tear preparations, gels, and ointments, topical

cyclosporine and punctum plugs. In addition, when planning cataract

surgery, the surgeon must evaluate the patient’s ability to comply with

the postoperative care regimen.

Conclusion

In this report we have discussed the possible factors

for corneal perforation following cataract removal surgery in a patient

suffering from Sjögren’s Syndrome. The effects of severe dry eye may be

potentiated postoperatively due to interference with lid mobility and

corneal denervation, reducing blink rate and post operative treatment

with topical NSAIDS and steroids. We hope to raise surgeon’s awareness

about the importance of proper evaluation of a high risk patient before,

during and after surgery. Meticulously caring for the epithelia may

guarantee good results in high risk patients.

Take home message:

- The effects of severe dry eyes may be potentiated postoperatively due to interference with lid mobility and corneal denervation, reducing blink rate and post operative treatment with topical NSAIDS and steroids.

- It is important to consider close observation of patients with any severity of dry eyes.

- Educate patients about the importance of complying with eye drops and attending follow-up

For more articles in JOJ Ophthalmology (JOJO) please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojo/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment