JUNIPER

PUBLISHERS- JOJ Ophthalmology

Abstract

Purpose: To report novel optical coherence tomography findings in a case of anti-α-enolasecancer associated retinopathy.

Observations: An elderly female presented with

bilateral decreased vision and a recent diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma.

Optical coherence tomography demonstrated bilateral loss of outer

retinal structures and macular edema. Serum testing found antibodies

against α-enolase and 82-84kDa proteins. Outer retinal structures showed

recovery, macular edema resolved and repeat anti-retinalantibody

testing became negative following cancer therapy and topical

difluprednate treatment.

Conclusion and importance: Cancer associated

retinopathy is a paraneoplastic disease that results in damage to

retinal structures through an autoimmune response. The damage is

generally considered to be irreversible however, in rare cases, such as

observed here, retinal structures may demonstrate recovery after

treatment.

Keywords: Cancer associated retinopathy; Optical coherence tomographyIntroduction

Cancer associated retinopathy (CAR) is a

paraneoplastic disease in which retinal degeneration occurs as an immune

response to cancer antigens sharing homology with endogenous retinal

proteins [1].

Past studies have found various retinal proteins to be antigenic, which

include recoverin, α-enolase, arrestin, and transducin [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/245316532].

The inhibition of enolase, a glycolytic enzyme, results in metabolic

disruption of retinal cells and the induction of apoptosis [3].

Anti-α-enolase autoantibodies are capable of accessing tissue and

targeting ganglion cells, Muller cells, and photoreceptors. It is

believed that death of retinal cells is an irreversible process. We

report a patient with gynecologicalCAR who experienced objective

improvement in photoreceptor architecture following treatment of her

underlying malignancy.

Case Report

An 80 year Hispanic female with a history of chronic,

bilateral Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada associated uveitis presented to the

Casey Eye Institute Uveitis Clinic for a routine follow up visit. At

that time, she reported a newdiagnosis of ovarian carcinoma and had

started her first chemotherapy session consisting of carboplatin and

paclitaxel. Due to severe aortic stenosis, the patient was not a

candidate for surgical intervention. Her vision was 20/30 bilaterally

without evidence of active uveitis. Four months later she returned with a

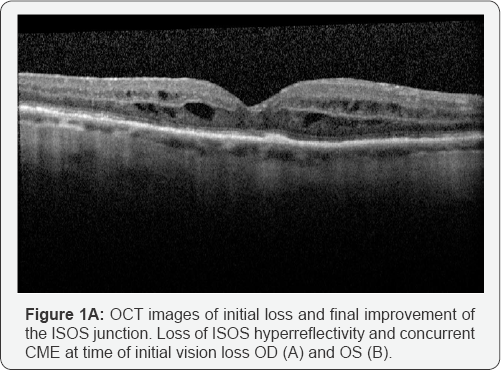

bilateral decrease in vision to 20/50. The patient underwent imaging

with macular volume scans centered on the fovea (Heidelberg Spectralis

spectral domain ocular coherence tomography (OCT) with eye tracking

software, Heidelberg, Germany) that demonstrated a disrupted inner

segment/outer segment junction (ISOS) and cystoid macular edema (CME)

bilaterally (Figure 1A & 1B).

Clinical and OCT findings were suspicious for CAR and anti-retinal

antibody testing was pursued. The patient declined local or systemic

immunosuppression specifically for her ophthalmic diseaseand continued

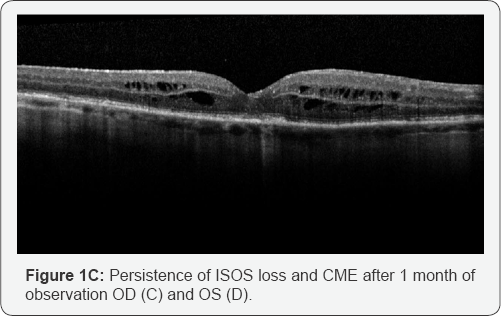

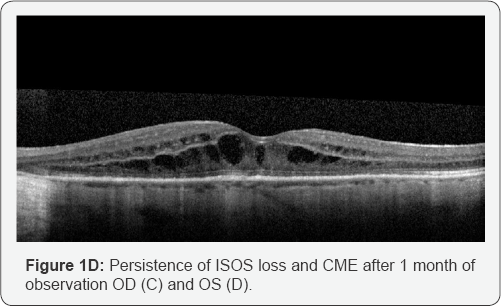

to undergo planned chemotherapy. One month later, her vision had dropped

to 20/50OD and 20/100OS. Repeat OCT mapped to the original images

continued to demonstrate loss of the ISOS junction and CME in both eyes (Figure 1C & 1D).

Serum tested for the presence of anti-retinal autoantibodies showed

antibodies against α-enolase and 82-84kDa proteins. Immunohistochemistry

of the patient’s serum showed positive staining of the photoreceptor

cell layer in human retina. The patient continued to decline periocular

injection or systemic immunosuppression and was prescribed difluprednate

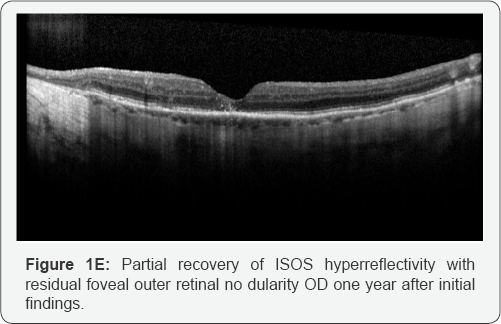

drops three times daily. Two months later, there was partial return to

normal reflectivity of the IS/OS junction on OCT and the CME had

improved. Six months later, there was resolved CME on OCT and the IS/OS

reflectivity returned to near normal in the subfoveal region. At this

time, the vision was 20/40 bilaterally. The patient was instructed to

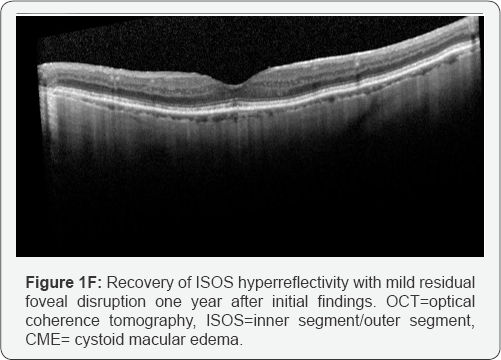

stop difluprednate drops. Over the following six months, the patient’s

visual acuity stabilized at 20/60OD and 20/50OS. There was no recurrence

of CME and the OCT showed normalized IS/OS reflectivity except in the

fovea where there was a stable elevated outer retinal lesion OD and

near-normalized ISOS reflectivity in the left macula except in the fovea

(Figure 1E & 1F). Serum was negative for anti-retinal autoantibodies on repeat testing.

Discussion

Anti-retinal autoantibodies can be detected in both

retinopathy patients and healthy individuals. Individuals with

gynecological CAR have a higher proportion of seropositivity than normal

individuals [4,5].

Our patient became symptomatic after diagnosis of ovarian cancerand

initiation of chemotherapy treatment. Autoantibodies may be present

before the diagnosis of cancer, but it is not until they breach the

blood retinal barrier that symptoms become evident [4].

Although the presence of anti-retinal autoantibodies can occur in

normal patients, high antibody titers are a better indicator of

retinopathy [5].

Anti-enolase autoantibodies affect the catalytic activity of the enzyme

thus depleting glycolytic ATP, increasing levels of intracellular

calcium which then induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis by the

activation of its key elements [3].

The loss of outer retinal structures and retinal

atrophy observed in autoimmune retinopathy arefrequently thought to be

irreversible [5,6].

Partial recovery of SD-OCT outer retinal changes in a patient with CAR

after treatment with rituximab has been reported, which suggests that

therapy targeting B cells and consequently reducing production of

anti-retinal antibodies may be beneficial [7].

Our patient showed improvement of the reflectivity of the photoreceptor

IS/OS junctiondespite only local therapy with difluprednate, which was

started to treat CME and reduce local inflammatory damage, but unlikely

to significantly affect autoantibody production. We hypothesize that the

prompt initiation of chemotherapy may have contributed to the patient’s

improvement by possibly decreasing tumor expression of enolase and

diminishing the production of anti-retinal autoantibodies or that

chemotherapeutic treatment non-specifically immunosuppressed antibody

production.The recovery of outer retinal structures in the present case

corresponded to anti-retinal antibodies no longer being detected in the

patient’s serum, supporting a pathologic role for autoantibodies in our

patient.Treatments that may limit the production of anti-retinal

antibodies such as rituximab should continue to be studied for efficacy

in CAR.

The history of prior uveitis is a potential

confounder to our findings; however, the patient did not demonstrate

active inflammation during this follow up period. The presence of CME

may also confound the ability to image the outer retina; however, we

observed patchiness of the ISOS junction outside of regions of retinal

edema indicating the outer retinal changes were not a sequel of CME

alone. CME is not a common manifestation of CAR, more frequently

observed in non-paraneoplastic autoimmune retinopathy [8], but previous case reports of CAR-related CME suggest it is responsive to steroids, as was observed in our patient [9].

Unfortunately, the patient declined additional objective testing

(visual fields, electroretinography), which would have allowed further

clinical correlation.

We report a patient with CAR who experienced

objective improvement in photoreceptor architecture following treatment

of her underlying malignancy, a novel observation previously reported

only following rituximab therapy. We also note the successful treatment

of CAR-associated CME with topical difluprednate, suggesting an

alternative therapy to previously reported treatments with periocular or

intravitreal steroids.

Conclusion

Damage to retinal structures from CAR can be

objectively captured by OCT and may demonstrate recovery after treatment

in rare cases.

Patient Consent

Consent to publish the case report was not obtained.

This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to

the identification of the patient.

Funding

P30 EY010572 from the National Institutes of Health

(Bethesda, MD), unrestricted departmental funding to the Casey Eye

Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY).

Conflict of Interest

JTR, PL, GA. The following authors have no financial

disclosures FJI, LJK, SSS, MS, KB. All authors attest that they meet the

current ICMJE criteria for Authorship.

For more articles in JOJ Ophthalmology (JOJO) please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojo/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment